See my piece in this book that was just published. The Revolution and Egg Salad Sandwiches, from The Times They Were A’Changing: Women Remember the 60s and 70s

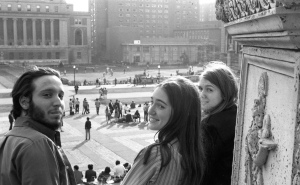

Columbia University in the City of New York, spring, Nineteen Sixty-Eight

In my Frye boots and Mexican dress, I strolled across the campus with two of my friends, “Bush” and “Norman.” This use of last names, reminiscent of prep schools or football teams, was a guy thing that didn’t include me, and I always chafed when I heard it. But it wouldn’t be until a few years later, when feminism surfaced and I joined a consciousness-raising group, that I could articulate the feelings it triggered: once again, excluded from the boy’s club.

Today that feeling was merely a twinge in the back of my mind, though, because we had a bond that went beyond gender. We were young people who knew that the war in Vietnam was wrong, and we had the brashness to believe we could stop it. We would become part of something much larger than our university or ourselves. Today we would become part of history.

The protests and rallies had been going on for weeks. We’d heard impassioned speeches by student leaders and radicalized Vietnam vets, we’d listened to Malcolm X, we’d talked and debated and agonized over our own roles, and now the three of us had made our decision. This was the night of “the bust,” and we were going to join the protest. The occupation.

What did it mean to occupy a building? My stomach fluttered and, to counteract the fear, I entertained the boys with an imitation of the old lady who stood on 114th Street, my street, and extemporized about current events. “Did you hear about that Michael Crudd?” I croaked, mimicking her voice, and we laughed uproariously. How incredible that anyone wouldn’t know the correct name of famous Mark Rudd, instigator and leader of our “revolution.”

As we made our way to our building, the campus was vivid in spring bloom, everything around us imbued with special meaning—the grassy terraces rimmed by distant buildings, the stone-paved plazas, the expansive tiers of stairs leading up to the grandiloquent Low Library. Presiding over all, the nine-foot statue of Athena, Alma Mater, resting on her throne. With her scepter raised in one arm, the lofty pillars of the library behind her, Alma Mater seemed the embodiment of the entrenched power that at this moment was so abhorrent to us. As we climbed the steps and passed beside her, Norman, jaunty and confident, flipped her the bird.

We had arrived at college with a respect for authority fostered in us as children, but now everything had changed. That spring, in rapid-fire motion, Martin Luther King, Jr. was shot and killed, the war in Vietnam escalated, villages were massacred, and our government became a symbol of oppression. We were angry. We wanted to end the war, and we wanted to end racism.

We advanced across the ponderous landscape, caught between a familiar impulse toward lightheartedness – this was, after all, the place where we hung out every day, talking, laughing, engaging the issues of the world – and the knowledge that what we were doing was scary business. There were rumors that the TPF, the Tactical Police Force, whose name alone carried images from science fiction, would come and arrest us. But what would happen? And how?

And where was Knox? Knox, the cheeky and charming self-styled revolutionary, better known to me as Greg, was my boyfriend. Knox, who stood up boldly at the rallies exhorting us to fight the good fight! Join the resistance! Don’t trust anyone over thirty! We would form a cadre, I fantasized. I would be the Tanya to his Che Guevara. But today, at the moment of truth, Knox was nowhere to be found. This demonstration was a big step into the unknown for me: I would be arrested, I would go to jail. Beneath my nonchalance, I was scared. But where was the love of my life?

“He’ll be here later,” Bush assured me.

The building we were heading for, Schermerhorn, was a massive edifice of stone and wood with high ceilings and an air of solemnity. But today the mood was anything but solemn, and when we arrived, the scene was chaotic. I had always been the dutiful student, arriving at class on time, handing in my papers, taking exams, but now there were no teachers or authorities, just us young people, huddling in groups, camping out with sleeping bags on the floor, rushing back and forth with swagger or bewilderment, making plans, announcing rumors. We were occupying the building.

But what were we supposed to do? What were the rules? There were no rules. We invented them as we went along. The student leaders invented them, the leaders being anyone who had the guts to stand up and present an idea, a plan. Our de facto leader Mark Rudd and his group occupied the center of university power, the president’s office in Low Library, where their photograph, later published in Life magazine, would become an icon of the protest movement. But here in Schermerhorn, although there were lots of speeches, lots of ideas, and lots of plans, there were no leaders.

I wandered around the building, searching for familiar faces, strolling over to look out the windows where the counter protesters, the ROTC boys, formed barricades to prevent deliveries of food and shouted hateful slogans. I drifted back to my seat on the marble staircase.

“The suits!” a boy shouted, running from the window. “The suits are coming!” A clutch of fear ran through the crowd. Ah, adolescence. How easy it was to know the good people from the bad. The bad ones wore suits. The suits, it turned out, wanted to persuade us to get out of there before the police came. But of course we couldn’t do that. We had a cause. And besides, we couldn’t trust people in suits.

“To the roof!” The call resounded. Bush and Norman were going to the roof. Did I want to come? What for? I asked. To watch for the pigs. And it’s really cool up there, they said. Have you never been? I had not. Intrigued, I followed them.

And it was cool on the roof. The view over the campus with its plazas and patterns, its greens and elegant buildings, was like the view from an airplane, with the New York skyline shimmering in the twilight and a sliver of red cloud across the horizon. The people on the ground, protesters, counter-protesters, professors trying to reconcile the two, onlookers, university officials, were ants scurrying to and fro on the face of the earth. We were all just tiny creatures in a larger universe that would go on, whatever we did.

Bush and Norman went directly to the edge of the building and sat with their feet dangling over. “Are you nuts?” I said, “That’s four stories high!” They laughed and pooh-poohed my concern, but I hovered at a safe distance behind, and when my anxiety intensified, I went back down the stairs.

And now I was hungry.

In spite of the barricade, food had been smuggled in, and a group was gathered around a table set up in the hall. One girl, tall and slim, with short dark hair, stood in front of a giant bowl filled with dozens of hard-boiled eggs. “Can I help?” I asked.

“No, this is a snap,” she said, and proceeded to take two knives, hold them inside the bowl and, with quick motions, cut up all those eggs in a few minutes. Wow. I’d never thought to chop eggs like that. As she chopped, she gave orders to the others: put the sandwich bread there, get the drinks from the cooler, set out the paper plates. She had flair and buoyancy, she was super-efficient, and she was doing something important for the revolution. This girl, I thought, she doesn’t worry about what people think. She isn’t shy and self-conscious, doesn’t second-guess herself like I do. This is the real Tanya. If I could have that kind of confidence, I, too, could take charge, be a leader of the revolution.

After we ate, there was more milling around, more talking, more announcements: “They’re coming at six!” We scurried to our positions and sat in lines along the hallways like we had for the air raid drills in elementary school. We were instructed in nonviolent resistance: Go limp. Just let them drag you. Whatever you do, don’t get up.

They didn’t come at six.

“They’re coming at seven-thirty!”

They didn’t come at seven-thirty.

Our conversations jigged back and forth between stories about jail to the silly jokes of punchy kids half-scared, half-exhilarated.

Knox still hadn’t showed. Knox never did show up, and perhaps this was the beginning of his unmasking, the ending of my fantasy. But by this time, I didn’t miss him. Each moment was loaded, full of elation and anxiety as I sat with my comrades and sang We Shall Overcome.

And then it happened. In the middle of the night, when we had all just drifted off to sleep, the cry came, “They’re here!”

Outside the window the sight was more chilling than any I had imagined: A line of men in helmets and riot gear and lit by a string of eerie spotlights advanced toward us, an army in the night.

As we sang We Shall Not Be Moved, the TPF knocked in the doors.

“Get up!” they ordered. “You’re under arrest!”

No one got up.

Again they ordered us up. No one moved.

They began to drag the boys, who were closest to the doors, throwing them outside like sacks of potatoes. They worked their way down the hall, and when they got to my friend, whose name was also Nancy, the officer, middle-aged and puffy, bent over and looked at her with a big sigh. Nancy was a beautiful, angelic-looking blonde. “Aw, come on, sweetheart, just get up,” he pleaded.

Nancy, stone-faced, didn’t budge. He dragged her out the door. I was next. I went limp and found it painless. They were gentle with us girls. When we got outside, we stood up and were herded into paddy wagons.

Watching Manhattan go by through the window grills of a paddy wagon, twenty of us packed onto benches meant for ten, felt surreal. This was our city, these were streets we roamed and explored freely, and now we were prisoners. No longer the privileged college students, now we were the faces we had seen on the other side of those paddy wagons, the faces of the disenfranchised.

As we were escorted into “the Tombs,” New York City’s prison, we stood waiting while a line of prostitutes, jaded women in high heels, short skirts and lots of makeup, was led in beside us. As they passed, they looked at us scruffy students with a mixture of humor and commiseration. The police then took us into a room where we were charged, and as we stood in a line facing the policemen, we were shocked to see that one of the boys had a line of blood running down his face. At the same time another boy muttered a sarcastic comment about police violence, and one of the officers went red in the face, raised his club and charged at him. “What did you say?” he shouted. “Who you calling violent?” We froze, exchanging furtive glances and saving this incident to recount later.

We were herded into cells, all seven hundred of us, the largest population the “Tombs” had ever held, twenty-five of us girls in a two-woman cell. A matron pulled us out one by one and over to the next cell where she stuck a gloved finger up our vaginas and rectums, examining for drugs. Sophisticated as we were in political discourse, we didn’t have the words or even the concepts to talk about this feeling of violation. We stayed there all night, sleeping in shifts, not knowing how long we’d be there, running on adrenaline, fear and a new solidarity, the solidarity of the oppressed.

The next morning we were arraigned and released. The Tombs just didn’t have the capacity for all of us. Only later did we learn about the police who, after the bust on campus, went on a rampage, chasing down and beating bystanders with their Billy clubs. The bad people, we now understood, wore police uniforms.

I went back to my student life, shaken and sobered, but the University remained in upheaval and the country unsettled for some time to come.

I didn’t stay with Knox and never became another Tanya, though I did participate in a few more protest marches. But after that and for the rest of my life, when I make egg salad sandwiches, I put the hard-boiled eggs in a bowl, chop them with two knives, and remember that night at Columbia.